In the midst of a transformative era in American rock music, 1974 stood as a powerful milestone, echoing the unrest and revolutionary spirit of the preceding decade while heralding the arrival of new, intense sounds. Amid this evolving landscape burst forth Ted Nugent, already celebrated for his electrifying guitar work with The Amboy Dukes. While Nugent’s reputation was firmly established, it was the raw, evocative final track on the band’s last studio album, Tooth, Fang & Claw, that carved an indelible legacy: the legendary, thunderous anthem, “Great White Buffalo.”

Unlike typical chart-topping singles engineered for radio appeal, “Great White Buffalo” deliberately eschewed commercial formulas. Initially, it failed to register on major U.S. singles charts, living primarily as an album track before blossoming into a live concert sensation. But its true power lay far beyond commercial success. This song resonated profoundly with listeners attuned to the deeper cultural layers of America’s history—especially those aware of the environmental and social upheavals that marked the mid-20th century. It became a rallying cry, an emblematic deep cut that not only defined Nugent’s artistry but also stood as a historic testimonial to a sobering, often overlooked narrative.

The genesis of “Great White Buffalo” is rooted deeply in the mythology of the American West and a profound empathy for Indigenous peoples. Nugent himself has described the creation of the song as a spiritual overflow, akin to a “stream of consciousness.” Reflecting on the origins, Nugent explained,

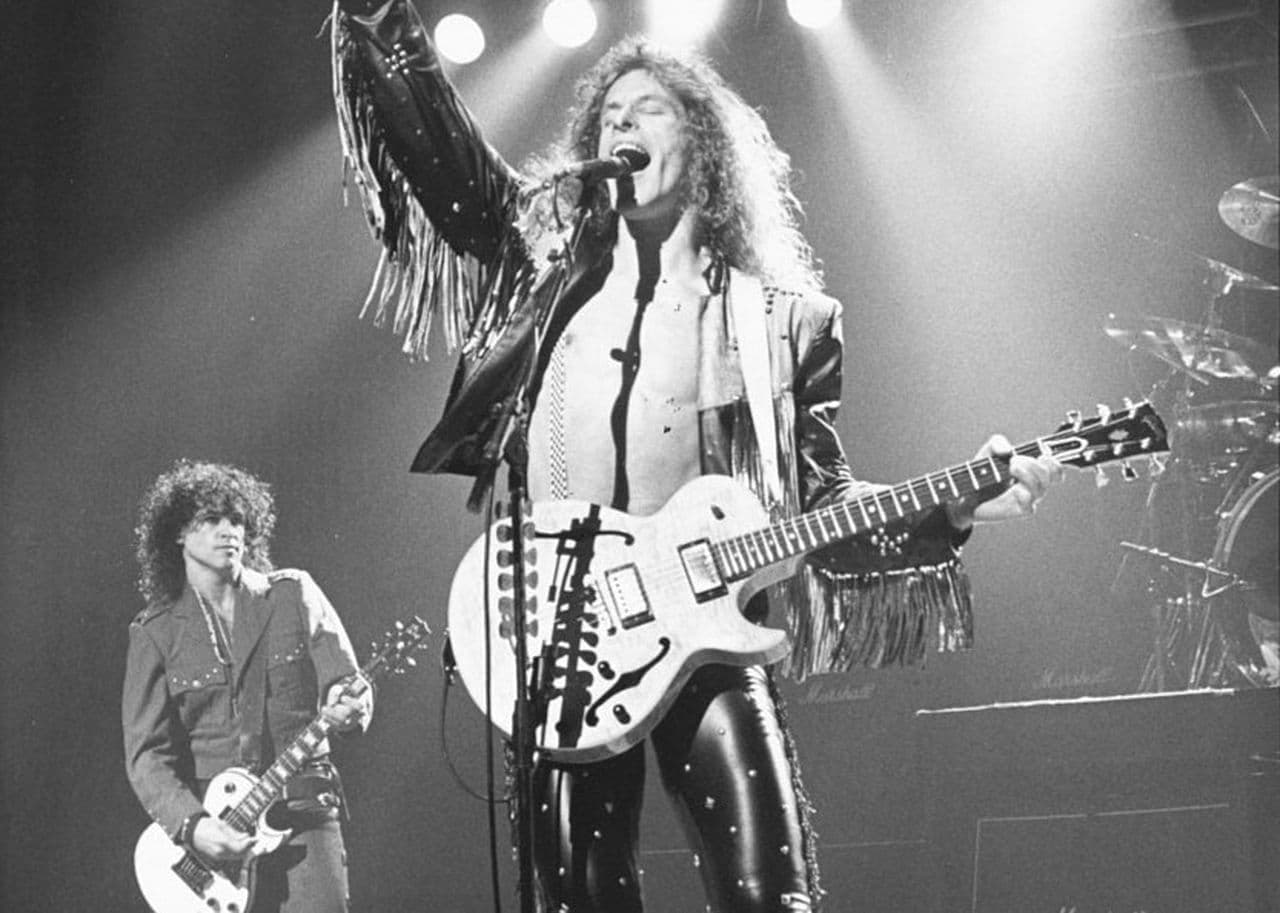

“It was as if the music just poured out of me—raw, urgent, like a cleansing of the soul, all born from the Gibson Byrdland guitar in my hands.”

The music itself—a driving, heavy riff with pulsating power chords—embodied this catharsis perfectly, becoming the vessel for a stirring narrative confronting the devastating near-extinction of the American bison. This event, deeply intertwined with the systemic oppression and erasure of Native American tribes, forms the backbone of the story conveyed through Nugent’s lyrics.

In Native American spirituality, the Great White Buffalo holds a sacred, almost mystical significance. More than a majestic creature, it symbolizes hope, renewal, and harmony. The lyrics unfold like a solemn, tragic drama:

“The Indian and the buffalo existed hand in hand / The Indian needed food and skins for a roof / But he only took what they needed, baby / Millions of buffalo were the proof,”

Nugent sings with mournful reverence. The narrative soon darkens, shifting from harmony to betrayal, indicting the destructive greed of European settlers:

“Then came the white man / With his thick and empty head / He couldn’t see past the billfold / He wanted all the buffalo dead.”

This blunt, emotional indictment stands out in the realm of mainstream rock, a bold and raw confrontation rarely heard so explicitly at the time.

Environmental and cultural historian Dr. Marjorie Black Elk, a Lakota scholar, emphasizes the song’s unique power:

“’Great White Buffalo’ is more than rock—it’s a sonic embodiment of Native trauma and resilience. Nugent captured a sacred narrative that many artists shy away from, and through his music, he demanded listeners to confront this painful history.”

For Nugent, the track was not only a musical expression but a call for recognition and respect toward Native communities and the natural world alike.

The finality of the song bears witness to perseverance and hope amid devastation. The figure of the Great White Buffalo emerges as a messianic protector, a mythical presence ascending “above the canyon walls,” eyes glowing with determination, poised to defend and restore the shattered herd. The tone is one of defiance and survival: a primal scream demanding justice and reverence for life. As music critic and Indigenous rights advocate Joseph Little Feather puts it,

“The Great White Buffalo represents the spirit of endurance—the refusal to be erased despite centuries of oppression. Nugent’s anthem is a bridge connecting rock music with a history often silenced.”

For listeners who lived through the 1960s and ’70s, those who witnessed the rise of the American Indian Movement and fought alongside the burgeoning environmentalist voices, the song carries a heavy emotional weight. It is not just a powerful rock track but a nostalgic and evocative reflection on lost innocence, a remembrance of resistance, and a soulful tribute to the enduring spirit of Indigenous America. Music historian Jonathan Weaver offered insight into the song’s cultural significance:

“It stands as a time capsule. Within the chords and lyrics, you hear the conscience of a generation wrestling with its history and its responsibilities.”

Ultimately, “Great White Buffalo” transcends its original context as a rock album track. It remains a monumental ode to Indigenous hope, a fierce, elemental voice from the American plains that continues to resonate, a timeless anthem illuminating the profound connection between people, history, and the land.