Introduction

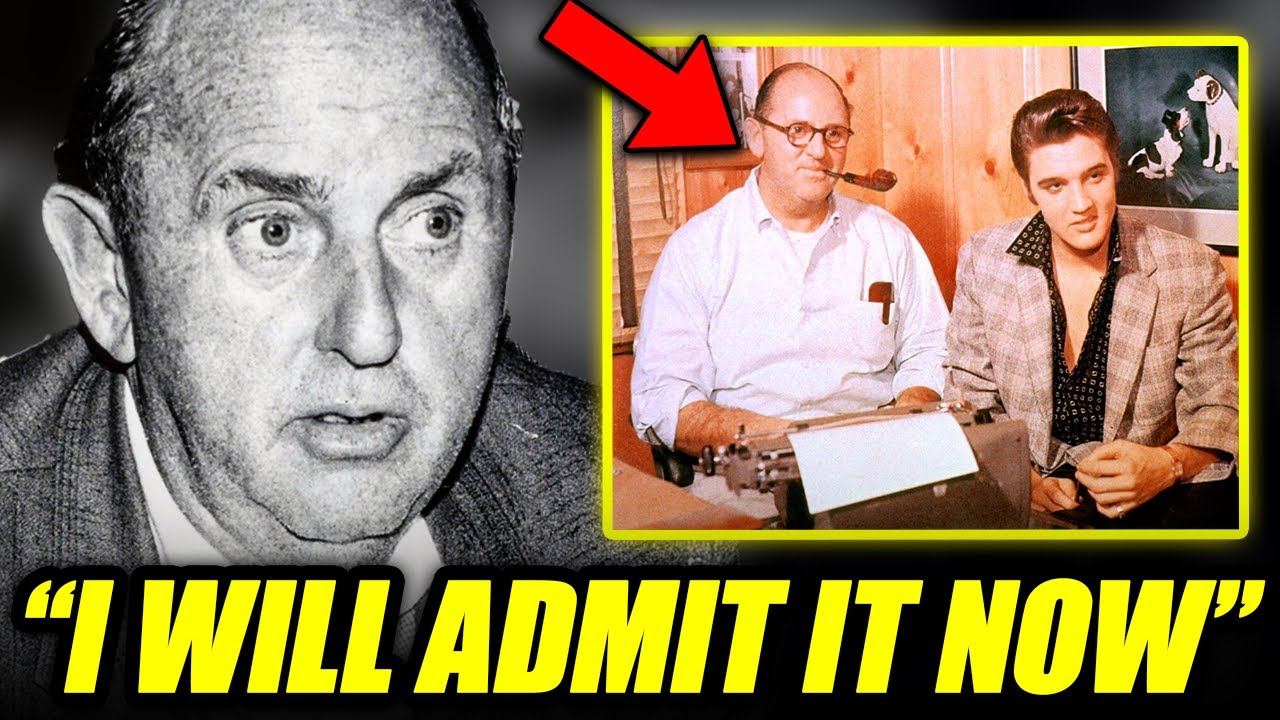

LAS VEGAS, NV — To millions around the world, he was Elvis Presley, The King of Rock and Roll — a blazing comet of charisma, a voice that could melt hearts and shake the earth. But behind the rhinestone jumpsuits and the blinding spotlight stood one man pulling the strings: Colonel Tom Parker, the self-made “showbiz genius” whose iron grip shaped both Elvis’s rise to immortality and his slow, tragic fall.

In newly resurfaced documentary footage, insiders paint a chilling picture of manipulation, greed, and control that would ultimately consume the world’s brightest star.

“Elvis wasn’t just managed,” said Jerry Schilling, one of Presley’s lifelong friends and a member of his inner circle. “He was handled, packaged, and sold — over and over again. Parker saw him not as a man, but as a product.”

For decades, Parker was portrayed as the mastermind who built the Elvis empire — the man who transformed a shy boy from Tupelo into a cultural phenomenon. But behind the curtain, his methods were far from glamorous.

“He was a carnival man through and through,” revealed Dr. Linda Patterson, a cultural historian featured in the video. “He came from the world of sideshows, of cheap tricks and ticket sales. To him, everything — even Elvis — had a price tag.”

Born Andreas Cornelis van Kuijk in the Netherlands, Parker arrived in America illegally and reinvented himself as a Southern “Colonel.” His showbiz instincts were unmatched. He negotiated groundbreaking deals, from RCA Records to movie contracts, and flooded stores with Elvis-branded merchandise — lunchboxes, perfume, dolls. It was a marketing revolution. But for Presley, that revolution came at a devastating cost.

Archival records and interviews reveal Parker’s staggering 50% commission, an arrangement virtually unheard of in the industry.

“Every time Elvis sang a note, half of it went into the Colonel’s pocket,” said Schilling. “He was gambling away millions while Elvis was killing himself trying to make more.”

Parker’s notorious gambling habit became a shadow over Elvis’s career. When the Colonel lost big in Las Vegas, new shows were booked almost overnight.

“It didn’t matter if Elvis was sick or exhausted,” an unnamed Memphis Mafia member recalled in the film. “Parker would bark, ‘The show must go on.’ That wasn’t advice — that was an order.”

By the late 1960s, Presley’s body was showing the strain. The energy that once electrified crowds was being propped up by a cocktail of prescription pills — uppers to stay awake, downers to sleep, and painkillers to endure the relentless schedule.

“He was running on fumes,” said Patterson. “And Parker just kept lighting the match.”

The pressure reached its peak during the legendary Aloha from Hawaii concert in 1973. Broadcast via satellite to over a billion people, it was billed as Elvis’s grand triumph. But backstage, the King was trembling, pale, and heavily medicated.

“Elvis looked like a god under those lights,” one crew member whispered in the video, “but up close, you could see the sadness in his eyes. He was a man trapped in his own myth.”

When the cameras rolled, Parker was in the control booth, barking orders and counting profits. He had turned his star into an international spectacle — and a financial lifeline. But the cost of that spectacle was Elvis’s health, freedom, and peace of mind.

As the 1970s wore on, Presley’s condition worsened. His face bloated, his speech slurred, and his spark dimmed. Yet the machine never stopped. Parker continued to book tours, sell records, and license the Elvis name.

“He didn’t care that Elvis was dying,” Schilling said quietly. “He just cared that the checks cleared.”

In his final years, the King was isolated inside Graceland, surrounded by sycophants and controlled by prescriptions. Late at night, he would sit alone at the piano, singing gospel songs from his youth — the only music Parker couldn’t monetize.

“Elvis was always searching for love and trust,” Patterson reflected. “But the one man he trusted most was the one who used him the hardest.”

When Elvis died in 1977, the Colonel wasted no time turning the tragedy into another business opportunity. He sold image rights, organized tribute tours, and stayed on as a consultant for the Presley estate — profiting from the very legacy he had drained.

For fans, the myth of Colonel Parker remains as divisive as ever: Was he a visionary who gave the world its greatest icon, or a manipulative puppeteer who traded a man’s soul for fame and fortune?

As Schilling concluded in the final moments of the film, his voice breaking:

“Without Parker, there’d be no Elvis Presley.

But without him… maybe Elvis would still be alive.”